Beyond the Balance Sheet: Financial Due Diligence for Grantmakers

By Alfonso Perillo and Pamela Labonte Maksy

Online charity rating systems are a good compliance tool, yet financial due diligence for grantmaking does not begin or end with that search. Sound financial analysis is possible when grantmakers: (a) know their selection priorities, (b) focus on the information they need – often found online, and (c) confidently go beyond the collection of reports for information.

After all, due diligence is important not only for compliance reasons but also for making sure that a grant-recipient has the financial capacity to carry out the funded program.

So, what should a grantmaker do before diving into the reports?

Identify financial attributes that make sense

Rather than dive right into the financial data and start calculating ratios, first identify the attributes you desire of a prospective grant recipient. This will help you determine what financial data to collect and review.

When we ask what they are looking for in financial reports, grantmakers often say they want to be sure that grantees are financially sound and have good governance practices. They also want to find any “red flags.”

As stated, these attributes are hard to measure. What, for example, does financial soundness entail? Different definitions would require different analysis.

One grantmaker may define financial soundness as having enough cash to meet current financial obligation. He would likely focus on current and quick ratios. Another may define financial soundness as having a small amount of debt compared to its equity. She would focus on the organization’s debt to equity ratio.

The financial attributes sought from prospective grantees should also align with the grantmaker’s guidelines and philosophy.

If a foundation makes grants to startup charities with innovative programs, it makes little sense to evaluate a charity’s current ratio or debt-equity ratio, since these results typically appear unfavorable with new charities. In this case, evaluating a charity’s business plan and governance structure may yield more important indicators than its financial data.

For more thorough due diligence, consider using a set of attributes that uncovers what matters most to you. Although this not an exhaustive list, it provides a sample of attributes to consider.

- Programmatic efficiency

- Strong governance practices

- High level of transparency

- Strong liquidity

- Tax compliance

- Low debt

- High resource usage (e.g. utilizes excess cash reserves for programs)

Operationalize the financial attributes

Next, rank the chosen attributes in order of importance. You might have a high risk tolerance and be unconcerned about debt ratio. On the other hand, you might value strong liquidity versus reinvestment of cash reserves.

After ranking the attributes, consider weighting the scores, assigning a value to each attribute based on its relative importance. For example, applicants may receive a weight of 1 if they exhibit strong governance practices, such as the adoption of whistle-blower and conflict-of-interest policies. They may receive a weighting of 1 to 5 depending upon liquidity. Of course, tax compliance would always be weighted highest priority.

Once the desired attributes are listed and valued, operationalize them by defining what to measure and how to measure it.

For instance, if you value efficiency, determine the desirable ratio of programmatic expenses to total expenses. A word of caution here, since this ratio is heavily influenced by the method used to allocate overhead costs, ask prospective grantees to describe in detail their overhead allocation methodology, especially if you plan to compare organizations within a cohort.

Dig for qualitative indicators

In the courses we teach, we emphasize the importance of understanding both what is in the documents and also what qualitative indicators may be missing.

The audited financial statements state that they have been prepared in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles, but they say little about the entity’s strategic direction, the effectiveness of its leadership, and quality of its programs, or even the organization’s financial position at the current moment.

Remember too that the financial statements and 990 are historical documents. By the time a grant applicant submits these items with their application, the documents may be many months old, and things could have changed. To assess the current financial situation, grant reviewers need to know how to dig deeper.

Examine the substantive information found in the audit notes and in the Form 990 and its attachments. The audit notes will reveal whether there is pending litigation or related party transactions. The Form 990 and its schedules will provide information about governance practices.

For example, if having an independent board is a desirable attribute for a prospective grantee, you would operationalize independence by requiring that all board members be free from conflicts of interest with the charity.

While ‘independence’ using this metric is easily determined by evaluating the Form 990 responses in Part I, lines 3 and 4, we recommend digging deeper to examine responses to Schedule L and other corroborating responses in Schedule O. These schedules may indicate whether the charity has engaged in transactions with interested persons (Schedule L) and describe how the charity monitors independence.

Since there can be some subjectivity in the evaluation of what may appear to be objective criteria, such as independence, a grantmaker with multiple reviewers should make sure that qualitative data is evaluated consistently. This will ensure that scoring of the attributes is also done consistently.

With this scoring system in place, you are able to identify the documents that contain the needed data and begin to analyze.

Go beyond the reports, ask questions

Uncertainty about which questions to ask is a common problem faced by our clients and those who attend our workshops. Consequently, conducting financial due diligence can be a daunting task.

We encourage you to dig in. There is no substitute for practice. Do not hesitate to request a conversation with the charity’s financial officer; he or she will be more likely to have the answers you seek than the program director.

Expertise will come with experience, by consistently asking questions about financial data that you find confusing or inconclusive.

In summary

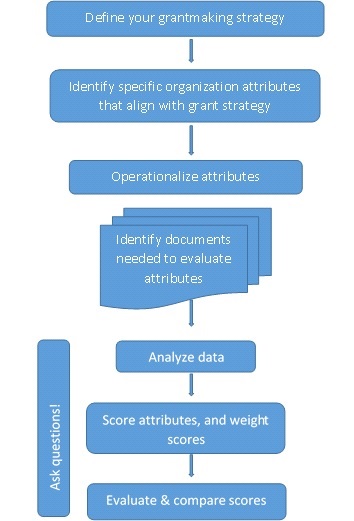

We advise an approach that starts with identifying the aspects of financial health that the grantmaker seeks in its grantees, rating those attributes in order of importance to the grantmaker, and operationalizing those attributes by identifying consistent measures.

The process of weighting the various attributes is helpful when comparing similar organizations within a cohort. Directing questions to the charity to help clarify its financial data will add further context and help grantmakers gain expertise and build a transparent relationship with the charity.

Financial Due Diligence: a model for grantmakers

About the authors:

Alfonso Perillo, CPA, CFE, MSW, is the nonprofit partner at Edelstein & Company. He works with a variety of nonprofit organizations and private foundations on their accounting, tax, and advisory needs.

Pamela Labonte Maksy is Chief Financial Officer at GMA Foundations. She helps private foundations and donors manage their financial and administrative functions to support their philanthropic goals.

Alfonso and Pamela co-lead workshops for grantmakers, including the popular Financial Statements 101, showing how to get a better understanding of a nonprofit’s health.